Jim Marshall – Music Biography

“I really like my old Marshall tube amps, because when they’re working properly (i.e., when the volume is turned up all the way), there’s nothing can beat them, nothing in the whole world.”

– Jimi Hendrix – Los Angeles, California (1967)

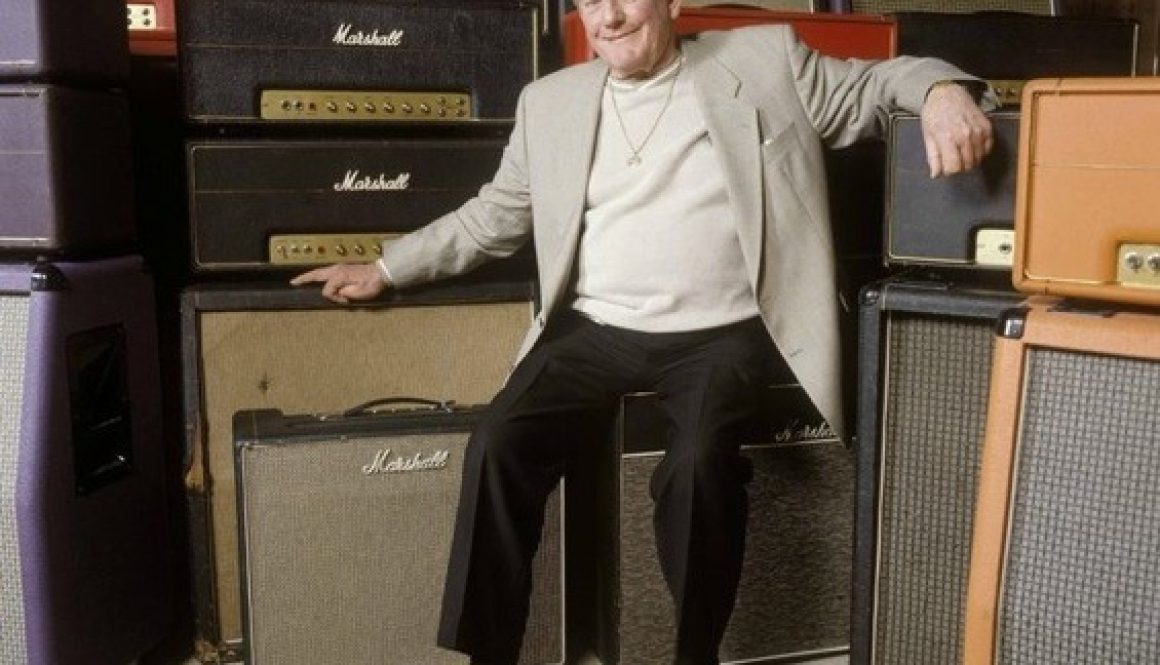

He may be known forever as “the Father of Loud,” but James Charles Marshall, creator of the Marshall Amp, had the true gift of a musician – he listened. By keeping in tune and in touch with those around him throughout his life, he created a musical legacy that will forever mark him as one of the “Godfathers of Rock and Roll.”

Jim Marshall was born in Acton, West London in late July, 1923. In his childhood, he suffered tuberculosis of the bones and spent a great deal of time in and out of Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital being treated for his condition. Naturally, his formal schooling also suffered and at thirteen, he began what would be a long string of jobs, from cannery work to baking to shoe salesman. But he kept reading and studying while working, so much so that when World War Two broke out and Marshall’s health rendered him unfit for military service, he managed to get hired by Cramic Engineering.

Marshall’s family was very musical and, in spite of his illness, he also took to music at a young age:

“I went to tap dancing lessons and a band leader whose granddaughter was in the same class as me heard me sing, he said he was playing locally at the Monapole, this was the largest dance hall in Southall. He asked me to come along and he would try me out. He thought that I sounded fine with just a pianist but may not be all right with a sixteen-piece orchestra. It turned out fine and from then on I was singing five or six times a week.

– Jim Marshall quoted in “The Jim Marshall Story

With so many people enlisting into Britain’s war effort, Marshall soon found himself doubling as a drummer in addition to his singing. And he used his newfound engineering skills to build himself a portable PA system so that his voice could be heard over his drumming:

“I was making ten shillings a night and because it was wartime, we didn’t have any petrol for cars, so I would ride my bicycle with a trailer behind it to carry my drum kit and the PA cabinets which I had made! I then left the orchestra to be with a seven-piece band and in 1942 the drummer leader was called into the forces and I took over on drums.”

– Jim Marshall quoted in “The Jim Marshall Story

Being a good musician meant a lot to Marshall, so in 1946 he began weekly drum lessons with Max Abrams. He studied hard and became so proficient that it wasn’t all that long before he was teaching in addition to gigging. In 1949, by his own count, Marshall was teaching “about sixty-five pupils a week.” Among his many students were Micky Waller (who would play for Little Richard), Mick Underwood (who would team up with Ritchie Blackmore) and Mitch Mitchell (who would be part of The Jimi Hendrix Experience).

Between teaching and gigging, Marshall made a comfortable living and was even able to save aside enough money to start a business. Naturally, he went into music:

“Having taught so many drummers, I used to buy Premier drums from the Selmer shop in Charing Cross Road and sell them to my students. The manager said that it was rather silly spending all this money there so why didn’t I open up my own drum shop? That’s how I started in retail. Then the drummers brought their groups in, including Pete Townshend, and said why don’t you stock guitars and amplifiers, which I knew nothing about. This would have been July, 1960.

“So I took the groups advice and they said they wanted Fender and Gibson. They were usually Fender Stratocaster guitars and Tremolux amps as well as quite a few Gibson semi-acoustics such as the 335. It was what they wanted and Ben Davis, who was the boss of Selmer at the time who imported most of the top models, was worried about how much I was buying, but I had already sold what was ordered.

– Jim Marshall quoted in “The Jim Marshall Story

Marshall’s shop did well because he listened to and believed in his customers. Dealing with guitarists and, especially, bassists, led him back to his work in engineering:

“In 1960 I started building bass and PA cabinets in my garage because nothing was really made as a column speaker, and I had the idea of using two 12” speakers. Also, there was nothing produced whatsoever in those days for bass guitar. The bass guitarists used to complain that they were being out-gunned all the time by the lead guitar and they asked me for help. So I started building bass cabinets.”

– Jim Marshall quoted in “The Jim Marshall Story

Between teaching and gigging, Marshall made a comfortable living and was even able to save aside enough money to start a business. Naturally, he went into music:

“Ken Bran used to come into the shop with his band ‘Peppy and the New York Twisters.’ At that time I think Ken was eager to stop travelling with the band and he said that if ever you want a service engineer don’t forget me. About a year later, after he’d worked with Pan Am, he came to work for me in 1962.

“It was Ken who said to me that it was rather silly to keep on buying in amplifiers when we could probably produce our own. So I told Ken to produce something and let me listen to it. We went all out to build a lead amp; I made the chassis while Ken and a bright young engineer called Dudley Craven designed and built the circuitry. I had already had chats with Pete Townshend, Brian Poole and the Tremoloes and Jim Sullivan and they said that they wanted something different in the sound because Fender was too clean, and listening to what they said imparted in my mind the idea of the sound they wanted.”

– Jim Marshall quoted in “The Jim Marshall Story

By 1962, Marshall introduced his first prototype – a fifty watt amplifier head paired with a compact speaker cabinet housing four twelve-inch speakers. It proved to be a big hit with his customers and soon his music store was refitted with a workshop where Marshall, Ken Bran and Dudley Craven were producing one new amplifier a week. Before 1964 was out, Marshall had opened a 6,000 square foot factory and hired sixteen people who were busy making twenty amplifiers each week. In 1965 he signed a world-wide distribution deal. And he would listen again to Pete Townshend who needed still more power and then put his team to work on designing the Marshall 100 watt amplifier.

Marshall Amps became the symbol of rock. Guitarists and bassists would pile speaker cabinets on top of one another, creating the now legendary “Marshall Stacks.” His amplifiers were used by Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page and, naturally, Jimi Hendrix:

“Jimi said that he wanted to use Marshall gear and that he was also going to be one of the top people in the world at this type of music. I thought he was just another one trying to get something for nothing, but in the next breath he said that he wanted to pay for everything he got. I thought he was a great character, I got on very well with him and he was our greatest ambassador. I saw him play about three times, and I saw him at the first sort of major concert which was at Olympia with Jimi Hendrix, The Move and Pink Floyd. I was very impressed by him as a musician; it was something new to me. I also went out with Ken and saw bands like The Who and Cream.”

– Jim Marshall quoted in “The Jim Marshall Story

As iconic as his amplifiers became, Marshall would get a huge boost from a very unlikely source: a fictional band. In the 1984 film, This is Spinal Tap, lead guitarist Nigel Tufnel (played by Christopher Guest), praises his Marshall Amp to the skies, pointing out its unique custom feature – the control knobs on his amp go all the way up to eleven, instead of the customary high setting of ten. Marshall, who had provided amplifiers for the film soon found himself making various models of amplifiers, such as the JCM900, that could go all the way up to twenty!

In real life, Marshall also could go up to twenty. In his own words:

“I’d done well from nothing, all these kids around the world were buying Marshall, so I thought it was about time that I started to put something back in for handicapped and underprivileged children.”

– Jim Marshall quoted in “The Jim Marshall Story

In his lifetime, he donated millions to the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital as well as to numerous charities in his home of Milton Keynes. In 2003, Marshall received the Order of the British Empire for “services to the music industry and to charity.”

Jim Marshall died on April 5, 2012 at the age of 88. Along with Leo Fender, Les Paul and Seth Lover (inventor of the humbucking pickup), he is considered a founding father of rock and roll. You can hear the mark he left whenever you go to a concert.

“I consider myself very fortunate to have known the late Jim Marshall. He was such a fantastic individual. Not only did he create the loudest, most effective, brilliant-sounding rock “˜n’ roll amplifier ever designed, but he was a caring, hardworking family man who remained true to his integrity to the very end. His work ethic was unequaled and his passion unrivaled.

“He took great care of me personally, as one of his loyal fans and Marshall Amp enthusiasts, ever since we first met in the early ’90s.

“At that time, he did the unprecedented: He had the first-ever Artist Model Marshall series designed for me when my Marshall amps were destroyed in a Guns N’ Roses concert riot in St. Louis in 1991. We had been friends ever since.

“Jim cared for all his customers like they were his family. He would do whatever it took to make sure an artist was completely satisfied and he made sure his staff did likewise. It was very important to him that Marshall quality and customer care was paramount.

“Jim’s passing marks the end of a very loud and colorful era. From Pete Townshend to Kerry King, Marshall Amplifiers have been behind every great Rock & Roll guitarist since the beginning. Marshall Amplification is one of the most enduring, iconic brands of contemporary music history.

“This industry will likely never see the likes of Jim again. But his legacy will live on forever.”

– Slash, quoted in the L.A. Times Music Blog, April 6, 2012

T Cat

May 2nd, 2012 @ 11:17 pm

Bought a SL 100 stack in 1970 with my student loan money. Me and that 100 eventually rocked with some of the greats all over the world. I hear it’s voice from time to time over the radio…so long ago. I still have the SL 100 brain and the sound is incomparable. Great instrument…great man.