Practice With Purpose -Turning Scales into Solos – Part 9

It’s time to take a little break to discuss a bit of philosophy when it comes to both scales and solos. After all, if you’ve come this far in our “Turning Scales into Solos” series, you should have some very important questions running around in your mind by now. If one of them happens to be, “I understand, at least in my head, the ideas we’ve been going over, but why do my fills and solos still sound like someone noodling around with a scale?” then perhaps we can answer that one once and for all.

And while the answer is positively mundane, it still might help nudge you in a direction that will help you become a better soloist (and player in general).

Are you ready? Here goes:

A scale is not, usually, a solo.

Take a moment to let that sink in before you gasp at how incredibly underwhelming (not to mention obvious) a statement this is. Take a second moment to get over the sarcastic replies that are filling your head as well.

And then think – how do you go about practicing solos? Many guitarists don’t really practice soloing at all. They practice scales and think that they are practicing solos. They will sit and work on getting their fingers to fly around on the fretboard until they are extremely proficient at it and then think that they are soloing. They aren’t. They’re just playing scales or sequences (or series, if you will – and more on that in a moment). Scales can certainly be used in solos and can be (and usually are) an important tool to create a good solo, but they are just one part of the big picture.

At their heart, the great solos we remember are like miniature songs, songs within songs, if you will. And part of what makes them both great and memorable is that they are sing-able. Or hum-able. They have melodies that stick in your head and you find yourself singing them or whistling them or playing air guitar while they’re running around in your brain. Scales are nice but not very exciting as melodies, unless you’re singing Do, Re, Mi or Joy to the World (the Christmas carol, not the “Jeremiah was a bullfrog” song).

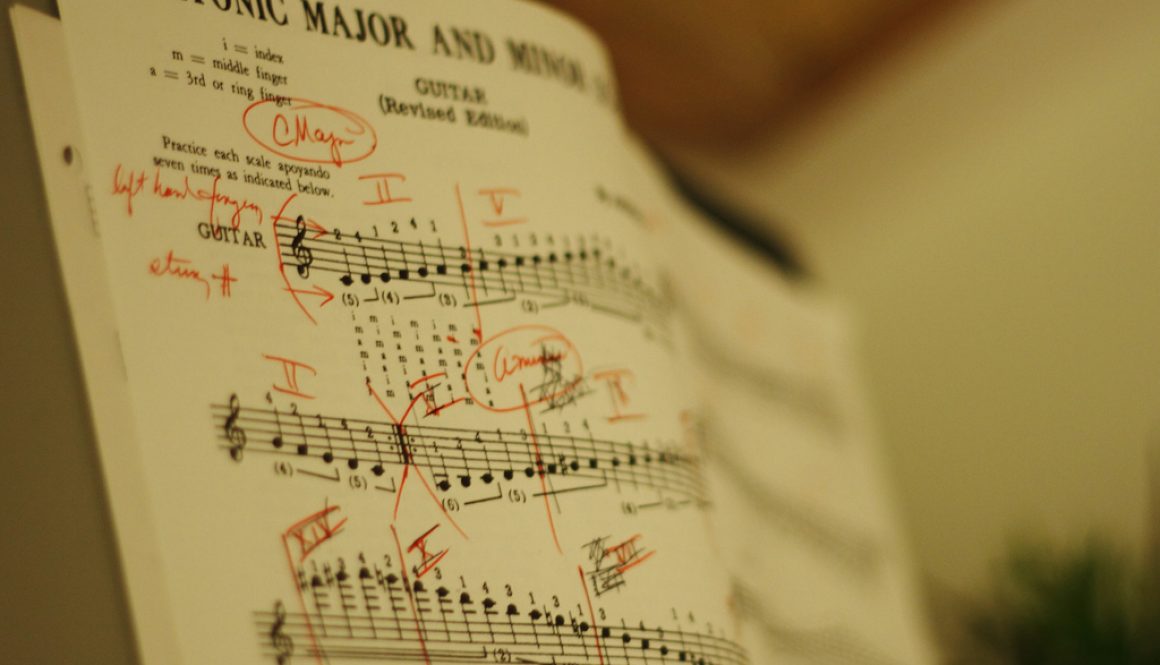

Scales move dutifully from one note to the next and we tend to practice them in steady, even rhythms in order to work on our speed. For instance, if we were to work on the C major scale, we’d probably do something like this:

See? Nice and even eighth notes. Maybe we’ll work on sixteenth notes or even thirty-second notes. After all, speed is what we’re interested in, right?

Melodies are interested in phrases and we’ve discussed the importance of phrasing at many points in this series. Just what do we mean by “phrasing?” Phrasing is how a line of music breathes. Take even a simple descending scale, change up it’s timing a little bit and voila! You’ve the first line of the aforementioned Christmas carol:

Even if you don’t play it or sing it, you can see from the different notes (and I’ve written out the counting for you to help you see it) that this isn’t even. It’s full of long notes and short notes and gives both the player and the listener places to take a breath.

Unless you make a deliberate effort to include phrasing and melodies as part of your practice routine when it comes to soloing, your solos are going to sound like the scales you practice. How can they not, since that’s what you’re practicing?

To be fair, a good number of beginners do get this and so they start to vary their practice routine by playing “series” or “sequences” instead of straight scales. A “series” or “sequence” is a slight variation on a scale. You might play the first four notes in order and then back up two notes, like this:

But if you’re observant (and again, you don’t even need to hear this if you’re paying attention), you can see that these are all eighth notes and therefore are all even. This, then, becomes an exercise about speed and not about phrasing. And there’s the trap. If you’re interested, truly interested in solos as solos, at some point you have to stop thinking about speed enough to become a student of melody and phrasing.

And that’s actually very easy, but not in an “easy to practice with a set format” way. It becomes a matter of putting together little melodic bits either from the scales you already know and practice, or from the melodies you can hear in your head while you’re playing.

For example, here’s the descending Am pentatonic, positioned at the fifth fret:

And here’s a very simple, yet elegant blues-style phrase (in swing eighths, so it’s counted out for you) that is basically a slight, incredibly slight, variation on the last example:

The use of the triplet on the second beat, plus the skipping of a note (or two) of the Am pentatonic scale, plus the occasional reversal of direction makes this sound a lot more like melodic, which makes it sound more like a solo.

Next time out, we’ll use a real life song to explore this idea further, but in the meantime you might find it helpful to go over a couple of old Guitar Columns here at on our site that explore what we’ve been talking about: Leading Questions and Picture in Dorian Gray.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief “sidestep” in our series and I also hope it helps you see that even though we often use scales as a starting point to soloing, they are two different creatures and we’re going to have to spend more time practicing making solos, which will help us make our solos sound less like scales. And we’ll tackle just how to “practice soloing” in Part 10 of this series.

As always, please feel free to write me with any questions. Either leave me a message at the forum page (you can “Instant Message” me if you’re a member) or mail me directly at [email protected].

Until next time…

Peace

Sylvester

March 24th, 2016 @ 1:10 pm

“And we’ll tackle just how to “practice soloing” in Part 10 of this series.”…absolutely great series – was reading along with rapt attention, but…there is no Part 10.

Rob

March 28th, 2016 @ 3:09 am

Hopefully part 10 is coming soon as I think this series is brilliant!

Matt

October 21st, 2014 @ 11:09 pm

Some great points for anyone learning to solo. I’d also add that soloing is like composition on the fly, check out some Zappa if you want to hear a great composer soloing.

tony

August 12th, 2013 @ 3:09 pm

trying to solo can’t find the rigth lessons

Chuck

December 8th, 2012 @ 10:10 pm

thank you for this lesson it really helped me you explain this more in detail than any one else.I have been trying to phrase for a while now in my solos.

Andy

July 12th, 2012 @ 8:50 am

I think you make a very important point here! When starting out on the journey towards improvisation, scale knowledge provides a nice and easy way to jump right in and not sound like crap; Especially with straightforward numbers, you can stay in a key and every single note will “sound in”…for the most part. There isn’t anything wrong with that. It feels good, builds confidence and allows you to practice as well as jam. However, like you implied, it can be a trap. Results are pretty immediate and it’s easy to practice speed and get results, the metronome is one of the few quantitative measuring sticks musicians have!

For me, the door to “real soloing” started when I began to learn chord theory and started looking at those scales in context. With a solid foundation of the scale patterns you can start to see them from a different and “more harmonic” perspective, which helps you build an actual melody that fits the song, instead of just an in-key “sequence”! To do that, you need to be able to see how the chords/triads from the song are “built” from the scale. When you can see and find the scale tones by number (I, IV, V, etc…) you can start to “follow the chords” and make musical sense instead of just noodling.