Guitar Tuning FAQ

Alternate and open tunings are a great way to explore more of the potential of your guitar. On our guitar tunings page you’ll find some great articles and lessons on alternate and open tunings, including some wonderful song lessons and arrangements. This page answers some of the most common questions beginners have about tuning. You’ll also find answers to more advanced questions further down the page.

-

Tuning a guitar is the single most important concept for a beginner to learn. At the same time it can often an early stumbling block. If your guitar is not in tune, you will never sound good. Rather than having your friends tune your guitar for you, you should learn how to do it for yourself.

There are several ways you can tune a guitar: by ear, with an electronic tuner, using another instrument such as a piano or a pitch fork. Most beginners will find it easiest to start with an electronic tuner. Don’t worry, tuning by ear is a skill that comes with time.

For step by step instructions on tuning a guitar you should read The First Time Ever I Tuned My Axe by Graham Merry. Another set of instructions can be found in How to Tune A Guitar.

It is also possible to tune your guitar using harmonic tuning.

-

If you have a chromatic tuner this can be easy. A half a step down is having every note “half a step” down – a half step is an interval and to the guitar it’s a one-fret distance. So, E becomes Eb and so forth.

From the low E to the high E it goes:

Eb Ab Db Gb Bb Eb

An easy way to tune down to half a step is to place a capo on the first fret and tune up to standard pitch, then, take off the capo and you’ll have half a step tuning.

-

A couple rules of thumb:

- Try to tune downward whenever possible. Too much stress on the strings is not good for the guitar or the strings (or you, for that matter). If you do tune up to a note, try not to go higher than three half steps.

- Use a capo. It’s much easier on your guitar to tune to Open D and then put a capo on the second fret to get your Open E. Ditto with Open G to get Open A. If you listen to the Rolling Stones’ Happy, you’ll find it’s in the key of B. Richards uses Open G tuning with a capo on the fourth fret.

- Remember that nothing is set in stone. But having said that, I will add that it is preferable to have your two lowest notes be the root and the fifth of your chord.

You can get a reference pitch by using another guitar that is in tune, a piano, a tuning fork, an electronic tuner or your computer. The easiest way to retune your guitar is to use a keyboard (which is hopefully in tune to start with). Most electronic tuners will allow you to tune to specific notes as well.

You can find more information on re-tuning your guitar in the article Open Tuning – Part I.

-

What we guitarists consider “standard tuning” has been around pretty much since the fifth and sixth strings were added to the instrument in the late 1700’s. And, artists being artists, “non-standard” or “alternate” tunings have existed for just about as long. For the sake of our discussions, we will divide guitar tunings into three categories – standard, open, and alternate.

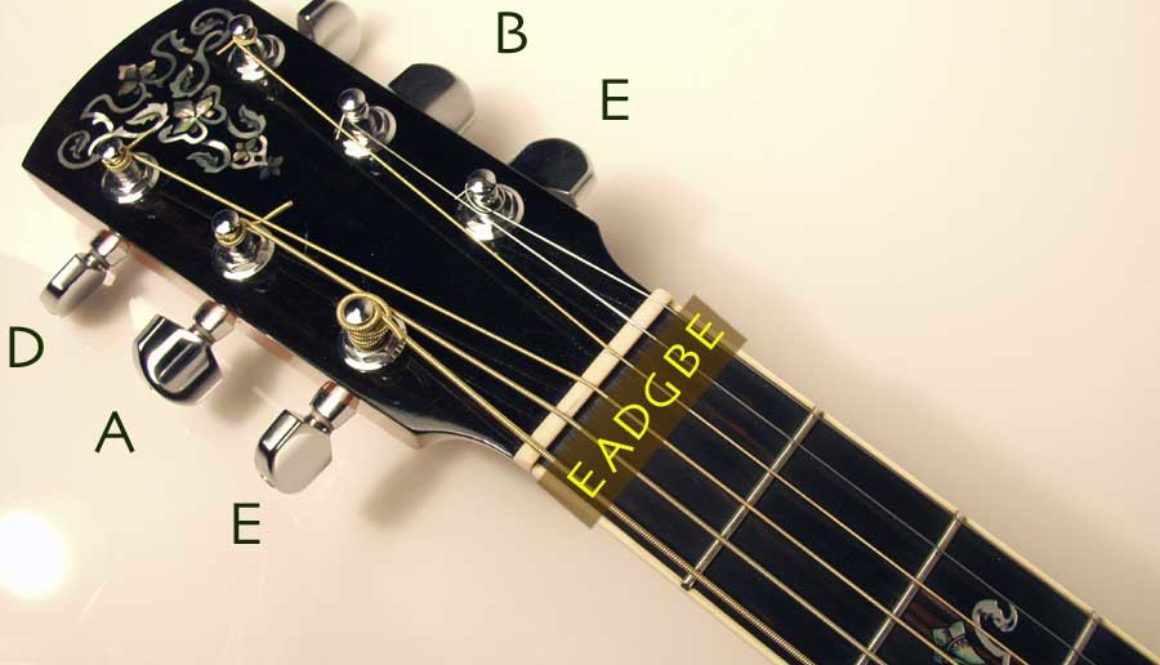

Standard tuning is what we were taught from day one (low to high or 6th string to 1st): E A D G B E

Standard tuning makes learning the guitar easier by allowing you to play the various chords in the same way that other people do. For more on standard and other tunings see the articles Standard Tuning (and Tuners) and Open Tuning – Part 1.

-

An alternate tuning is any tuning that is neither standard nor open. Any tunings that have the same intervals between each string are a kind of standard tuning, such as:

STANDARD

E A D G B EAlternate #1

Eb Ab Db Gb Bb EbAlternate #2

D G C F A DAlternate #3

Db Gb B E Ab DbAlternate #4

C F Bb Eb G CThose of you who play a lot of Nirvana, as well as other 90’s groups, will recognize these as “low tunings”. While they are indeed, by our definition, alternate tunings, they are simply transposed standard tunings. All the intervals between the strings are the same as they are in standard tuning. “Alternate #1” is tuned a half step lower than standard, “#2” a whole step lower and so on.

For more on altered tunings check out the article On The Tuning Awry.

-

Open tuning is when we tune the guitar in such a fashion that results in our getting a major (or minor) chord when we strum the open strings.

You will find more on open tunings in Open Tuning – Part I and Open Tuning – Part II.

-

Open tunings have been making a “comeback” of sorts lately, but they have always been a staple of serious musicians. Many fledgling guitarists are unaware that artists such as Keith Richards, Dave Mason, Richie Havens, Leo Kottke and Mark Knopfler have been using various forms of open tuning for years. Slide guitar players often tend to utilize open tuning; it suits their particular playing styles quite well.

Here are some basic open tunings:

STANDARD

E A D G B EOPEN C

C G C G C EOPEN C Minor

C G C G C EbOPEN D

D A D F# A DOPEN D Minor

D A D F A DOPEN F (used by Jimmy Page in Bron Y Aur)

C F C F A FOPEN G

D G D G B DOPEN G Minor

D G D G Bb DOPEN G Seventh

D G D G B FYou will find more about open tunings in the article Open Tuning – Part 1.

-

We’ve put together a list of different alternate tunings. This is by no means a definitive list of all the possibilities. We haven’t included any formal names on these tunings, but have made some notes about a few of them.

- E A D G B E – standard

- E B D G A D

- E E E E B E – Stephen Stills uses this in Carry On and Suite: Judy Blue Eyes. The fifth string is tuned to the sixth while the third and fourth strings are tuned to the E an octave above that (and an octave below the first string)

- E B E G A D

- E A D G C F

- E B B G B D – Ani DiFranco uses this in Not a Pretty Girl. Again both the fourth and fifth strings are tuned to same note

- E A D G# B E

- E A D F# B E

- E A D G B D

- D A D G B E – Drop D

- D A D G B D – Double Drop D

- D A D D A D

- D A D E A D – Not used by Jerry Garcia (at least as far as I know) (sorry, I couldn’t resist)

- D G D G A D

- D G D G B E

- D G D F# B D – yes, technically open Gmaj7

- C A D G B E

- C G D G B E

- C G D G C D – one of my favorites

- C G D G B D

- C G C G B E

- C G C G C D

- C G D G A D

It’s safe to say you could spend quite a bit of time looking into this. Find out more in the article On The Tuning Awry.

-

Tuning a 12 string guitar is a little more complicated than tuning a regular six string as there are twice as many strings to think about. There is the question of how to number the strings as well as tuning down in order to lesson the tension on the neck of the guitar.

For step by step instructions on tuning a 12 string guitar you should read How do I tune a 12 string guitar? You might also want to check out What are some good alternate tunings for a 12 string guitar?

-

Any alternate tuning that you’d use on a six-string guitar can also be used on a twelve string. Open G and D and DADGAD are especially nice as well as any that highlight finger picking patterns, such as CGDCGD.

If interested in tunings where the octave strings are not tuned in octaves, this can be done, but is extremely tricky to execute. This answer gets a little involved, so check out What are some good alternate tunings for a 12 string guitar?

How do I tune a tenor guitar?

Traditionally, tenor guitars were tuned like tenor banjos, that is, in fifths like a mandolin. From low to high: C G D A.

Like many things, you can have all sorts of different tunings. Celtic (Irish) musicians favor G D A E tuning (and that makes me wonder that the reason there are six tuning pegs is so that you can use different sets of strings…). Ani DiFranco uses all sorts of alternately tuned tenor guitar in her songs.

-

The easiest way to get into tune and stay there is buy an electronic tuner. These small and inexpensive devices can save you a lot of trouble, especially in live situations and noisy environments. While an electronic tuner is a great addition to your guitar case, you should not rely on them exclusively. Do not neglect learning the skill of tuning for yourself as it is great for developing your ear. See our lessons on ear training for more on that.

There are two types of electronic tuners. One is a quartz tuner and the other is a chromatic tuner. The quartz tuner can usually only tell you the notes for each of the strings on your guitar and displays its reading using a needle that sways back and forth. Because it uses a sensitive needle to read the tone, you might have to replace it after dropping it only once. A chromatic tuner on the other hand can withstand being dropped a few times as it has no moving parts. Chromatic tuners often include all notes including sharps and flats and usually allow you to calibrate them to some degree. They usually include input and output ports so you can plug in your guitar and tune it in spite of any noise around you.

For more on using an electronic tuner you should read The First Time Ever I Tuned My Axe by Graham Merry. More on the use of tuners can be found in How to Tune A Guitar.

-

This depends on which string you want to tune to C.

If it’s the sixth string (low E), then you want to tune it down two whole steps. The easiest way to check if you’re okay is to test it against the A(fifth)string. If you’re correctly tuned, then when you press the NINTH fret of the sixth string, you’ll get the A note (same as open fifth string).

If you’re going by a tuner. Just hold at the second fret and tune to a D. I usually go back and make sure the 2nd fret is precisely a D, the 4th is an E, etc. Tuning down your strings tends to make them slip out of tune more frequently.

-

This is essentially the same as tuning by what we’ll call the “normal” method (tuning the A string to the 5th fret of the E string, etc.). The difference is that you use the harmonic notes to tune between the strings. The easiest places to produce harmonics on your guitar are at the 12th, 7th and 5th frets. The thing that you may not know is exactly which notes are produced by harmonics.

This is not any more difficult than the “normal” tuning method. A lot of people use this method because you can let the harmonics ring while you tune the string. You can use both methods – the “normal” way to get in the general neighborhood and then harmonics to fine tune.

For a step by step guide to tuning using harmonics you should read: How do I tune my guitar using harmonics?

-

Different guitars bridge tune in different ways. Essentially, it comes down to this. On on end of the bridge (usually the side furthest from the neck) there should be a set of very small screws. These screws adjust where the string sits on the bridge. By turning these you are adjusting the intonation of the guitar. Some newer guitars use these in conjunction with a “nut-lock” which is a device that, in effect, clamps down the nut end of the strings to prevent them from moving.

You should adjust the screw in the smallest of increments, testing it frequently. You know that your intonation is off if the harmonic on the twelfth fret DOES NOT MATCH the open string. Usually they are not very far off, but if they are it affects the string up and down the fretboard. In other words, you sound like you’re in tune when you tune it normally, but then it sounds out of tune when you play full chords.

Two things to note: First, after you’ve fixed the string in question, it is imperative to check the other strings EVEN IF YOU DID NOT ADJUST THEM. Messing around with the intonation of one string almost always affects the other strings, even in a small way. It doesn’t hurt to check, especially if your guitar has a “floating bridge” (one that uses or can use a tremolo bar). This domino effect, by the way, is why it is never a good idea to toy around with alternate tunings on most electric guitars – you shoot the intonation to hell and then you spend hours getting things back into shape.

Second, this takes time and patience. Even people who do it a lot try to set aside time for this task when they can give it their undivided attention. If you’ve never tried it before it is bound to be frustrating. If you can’t hear or make out what you’re doing, then it is probably best to just bring it in to a music store and let someone do it for you.

And that’s another thing. It may not be a problem that you can fix. A slightly warped neck can also give you fits and no amount of tinkering with the bridge tuning will fix that. If you suspect you have such a problem, again bring it to someone at a shop. Save yourself the aggravation.

Anyway, I hope this helps. Without knowing the type of guitar involved this is about as good as advice as I can give you.

-

Have you connected the tremolo arm to the bridge?

The Floyd rose is a tremolo bridge, and basically acts as a movable bridge – both up and down. What makes the floyd rose system independent is that it can lock the string both at the bridge and the nut. When you connect the tremolo arm to the bridge, you can push/pull it down/up in order to shift the pitch either up or down. You can push and pull on a Floyd rose system and still get the same result, but the tremolo arm makes moving the bridge up/down much easier.

You can also find more information in the article Tuning A Floyd Rose (or other similar floating bridge).

-

There are two things you can try. Instead of 5th fret of six string to open of fifth, try 12th fret of sixth to 7th fret of fifth, etc. It’s the same notes, but one octave higher. This should be easier for you to distinguish.

Another thing you could try is tuning by harmonics. Sometimes people who normally consider themselves “tone deaf” are still able to hear the higher pitches of harmonics. If you do this on an electric guitar with the volume up a tad higher than normal you can actually feel it more than hear it.

You can learn how to tune using harmonics by reading the harmonic tuning lesson.

-

There can be a lot of reasons why your chords from the TAB sheet don’t sound the same. It can be something as simple as the TAB being wrong (this does happen – more than people think!) or that the TAB is written in a different key than the one in which song is actually played. Or that the recording of the song has been altered (sped up or slowed down) so that it is not really in tune with the real world.

It can also be a matter of the blues’ artist’s guitar being tuned differently. This is especially true if it is a slide guitarist – they tend to use open tunings (DGDGBD, DADF#AD, EBEG#BE, etc).

But more often than not it is a matter of voicing and chord embellishment than anything else. Say a blues song is in the key of A. Well, the TAB will usually list the chords as A, D and E. But the guitarist may chose other, “embellished” chords (that is, chords with the same basic triads but with added notes for flavor). Instead of an A, he may play an A7 and then add to the confusion by playing it with this voicing:

E – open

B – 10th fret

G – 12th fret

D – 11th fret

A – 12th fret

E – don’t playAnd then when he gets to the D, he may play a D7 or, better yet, a D9:

E – 5th fret

B – 5th fret

G – 5th fret

D – 4th fret

A – 5th fret

E – don’t playUnless your TAB is specific about the exact chord and chord voicing you can see that there are all sorts of different reasons why you will not sound exactly the same.

But that’s cool, too – this is what learning is all about.

-

We covered this question a little in the trilogy about ear training (specifically the third part Solving The Puzzle) but it bears repeating.

The first thing you have to do is to have your guitar in tune, period. And tuned to standard tuning. To do this you need a keyboard or an electronic tuner. Now for the most part this should allow you to play along with your CDs. There are, of course, a few exceptions to this:

- The song is in a different key than you’re used to or than it is TABBED out or notated in. For example, Three Marlenas by the Wallflowers is often written out in the key of D. But on the CD it is in Eb which is a half step up. The simple solution is to play a capo on the first fret and play in D. I usually try to find out what key a song is in before I worry about playing along with it. Again, in the column Solving The Puzzle, I go over the procedure of finding the key to a song.

- The guitars have been tuned differently. If you’re trying to play along with Pearl Jam or Korn or any of the bands these days that use guitars tuned down a half-step or a step or even more, then you’re going to have to make a decision to either do so yourself of to play in a different manner than that which is TABBED. For instance, if you wanted to play along with a Nirvana CD, it would be a good idea to have a guitar tuned down one step (low to high: D, G, C, F, A, D) for those songs which use low tuning.If you have determined that a song is in Eb, D, or Db, then you might want to listen to the chord voicings used in order to decide whether or not to lower your tuning. Or you could learn to play in these keys – it’ll make you a better guitarist in the long run.

- The recording has been sped up or slowed down. This does happen, especially with some of the older recordings. The Beatles and Bob Dylan, for instance, did this a lot. If you find that you cannot find the key of a song then the chances are that this is the case. What you have to do is to get close. Say you listen to Across the Universe on the Let It Be album and you find that the song is higher than C but not quite at C#. Then play ONE NOTE ON AN OPEN STRING that is part of the chord (in this case the high E string or G string will do) until it is in tune with the song. To check it – you should then be able to noodle around on the one string and sound fine but you definitely sound off on the other strings. Once you have this one string in tune you will have to manually tune the other strings to it (and I’m assuming you know how to do this) and then you will be in tune to play this one particular song.

-

For as long as there’s been the guitar, there’s been different ways of tuning it. What we think of as “standard tuning” has evolved over time. Our modern guitar came from the lute and lutes were tuned to fifths instead of fourths (I’m not the greatest historian, so please don’t take me to task).

Anyway, nowadays people use alternate tunings for all sorts of reasons. The most obvious ones are open tunings. This is tuning your guitar in such a way that you get a major or minor chord when you strum the open strings. We cover this in our open tuning columns on the Guitar Columns page, as well as in the Easy Songs for Beginners’ Lesson Happy and in the Intermediates’ Lesson Simple Twist of Fate.

Other alternate tunings are as numerous as one’s imagination. As to “why” one might use them, this can range from having a bass note that might not otherwise be available (Drop D, for instance, where the low E is tuned down to D) to creating a fingering arpeggio that would be physically impossible in standard tuning (such as David Crosby’s Guinevere). You can check out some of these ideas in our “Alternate tuning” articles on the Guitar Columns page – On The Tuning Awry, Cover Story and Alternate Writing Styles. The latter article discussed the use of alternate tuning as a way to get around writer’s block.

You might also want to check out the column A Celtic Air which discusses the use of DADGAD tuning in Celtic guitar playing.

-

There’s a lot of debate about this and I just don’t know. I’ve tried playing it with open G and the fingering is just really too hard. But after you wrote I thought about it some more and I have an idea. Since the guitar is tuned pretty close to open G anyway and since the chords, okay the fingerings, are done primarily on the second and fifth strings, why not tune the first string down to D, that is, EADGBD tuning? This way you can play it throughout the whole song much as you do the open D (fourth) string. I’ve tried this and it does work. Again, you can hear that it’s not the same but it does give more ringing strings and a nice overall tone.

You can try out the song in standard tuning in the Guitar Noise easy song lesson Blackbird.

-

When you strum the guitar without fretting any notes it will give you a D major chord.

Let’s do the open D tuning. First we take our standard tuning (low to high):

E A D G B E

and then we look at where we want to go:

D A D F# A D

You can see that the 5th and 4th strings (A & D) are going to stay the same. If you have an electronic tuner, this is going to be a breeze. Simply tune both the E strings (1st and 6th) to the D setting, just like you would your D string. If you don’t have an electronic tuner, then you tune both strings to the open D string, only an octave higher on the first string (this is the same as the 3rd fret on the B string)and an octave lower on the sixth string (when tuned correctly, your A string will now match the 7th fret of the sixth string instead of the 5th fret like it normally does).

To get the A on the second string, you can again go by the A setting on an electronic tuner, or use the octave of the open A string. This should now match the 2nd fret of the G string (instead of the 4th fret).

The F# is the only tricky one, and even that’s not too hard. You want to tune this string to the 4th fret of the D (fourth) string (instead of the 5th fret).

You should now be in open D tuning. When you strum the guitar without fretting any notes it will give you a D major chord.

-

C# tuning (so that when you strum the strings without fretting anything you get a C# major chord) and yes, there is such a thing.

Most people think of it as Db tuning (I think because “flat” = “down” or lower in our minds) but since Db is the same note as C# it is the same tuning.

Anyway you look at it, it’s a step-and-a-half lower than standard tuning, meaning it would look like this:

STANDARD:

E A D G B EOpen C#:

C# F# B E G# C#The easiest way to get there (assuming you don’t have an electronic tuner) would be to tune your 6th string down a step and a half. This would now be in tune with your open A string when you play the 8th fret of the 6th string (instead of the 5th). Once you have this string in tune you just tune it the regular way.

If you do have an electronic tuner that only works on the standard setting, then just tune the 3rd and 4th strings to their appropriate notes (B and E respectively) and then work your way to the outer strings. This will involve working “backwards” on the 5th and 6th strings, but it’s not that hard.

-

Believe it or not, this is simply a standard “Drop D” tuning. But after you get a drop D tuning, then every single string is tuned down an additional step. If you were to play your standard D chord in this CGCFAD tuning (across all six strings), you would be playing a C major chord.

Of course, just telling you to tune to drop D (simply tune your low E string down to D)and then tuning each and every string down an additional whole step is probably not that helpful, so you might want to try it this way:

- Make sure your guitar is tuned correctly to start with.

- Tune the A (5th) string down to G by matching the open 5th string to the third fret of the 6h string (instead of the fifth fret like you normally do).

- Once you’ve tuned the 5th string to G, you can then go and tune the strings above it in the normal manner (matching the 4th string to the fifth fret of the 5th string, etc). Essentially what you have done is to tune the first five strings down one whole step. Your guitar will now be tuned EGCFAD.

- Finally tune the low E (6th) string down to C. Your can do this either by matching it an octave lower than the 4th string (now tuned to C) or by matching the twelfth fret harmonic on the 6th string to the open 4th string.

By the way, if you’re interested in various alternate tunings and how to go about using them, then check out the article On The Tuning Awry.

-

Here’s a question from a recent email:

I am curious if you can answer this question with a reasonable degree of certainty or if not direct me to someone who can. I tuned one guitar to drop D and one to open G. I have gotten a 50/ 50 mix of friends telling me I can leave it tuned that way on the one hand and on the other hand I get told I need to retune them to standard every time I finish playing. Any suggestions?

And thanks for writing. I can definitely answer your question with some degree of certainty, but I will also tell you that this is one of those questions where people do have varying differences of opinion, and sometimes quite strong opinions at that. And usually, as is the case with most differences of opinions, these feelings are often based on some instance of personal experience. Someone might have a guitar that he or she keeps in open G all the time without any kind of problem at all. Someone else might have a guitar that he or she retuned to open G at one point and it caused no end of grief in terms of retuning, or perhaps some greater calamity was involved. It’s always good to ask “why” whenever you receive an answer that seems based more on an opinion than anything else.

Be that as it may, you should have no trouble keeping a guitar at open D or open G for any length of time. Forever, if you so desire. Neither of these tunings involves tuning strings higher than they would be if they were tuned to standard tuning, so you’re not causing undue stress on the neck or on the saddle (if it’s an acoustic guitar).

Open E and open A are a whole “˜nother kettle of fish. Both these open tuning involve tuning a number of strings higher than they would normally be. Because guitars are designed for standard tuning, keeping these strings high than normal for an extended period of time (extended usually meaning “days” and not “hours”) can cause unwanted stress on your guitar.

This discussion is also common among people who own twelve-string guitars, by the way. One faction will say that you should keep your twelve string tuned a half-step or full step lower so as not to stress the neck. The other side says it’s perfectly fine to keep it in standard tuning all the time. There are valid arguments for both sides and usually it becomes a matter of personal taste and experience.

There are some factors to keep in mind, though. (aren’t there always?) as laws of inertia apply here. If you keep a guitar in open G or open D for an extended period of time, your instrument is going to go through a period of adjustment should you decide you’ve got to play it in standard. It may initially not hold its tuning and need some bit of adjustment until the strings get used to being stretched to normal tension again. As silly as it may sound, if the strings are old or have worn spots, you run the risk of breaking them when you retune up to standard. Constantly putting your guitar into an open or alternate tuning and then going back to standard does put wear and tear on your strings. So it’s a good idea to have spares handy.

I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For

Bono Tip: What do you need help with? Tweet it to us at @guitarnoise1 and we’ll see what we can do.