Before You Accuse Me – The Blues – Part 1: Structure and Shuffle

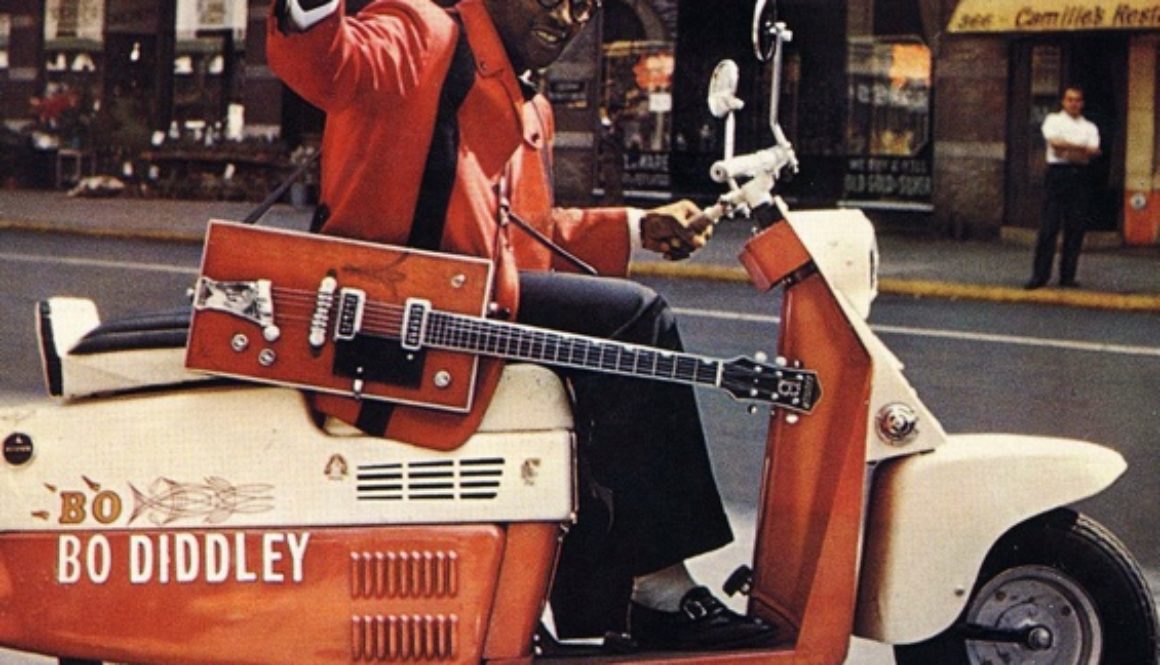

Today we’ll be branching out into three chord songs in a big way. We’ll do this by learning a standard blues song, Before You Accuse Me, written by E. McDaniel, known to the world as Bo Diddley. But we’re also going to be examining the theory behind what is known as “Twelve Bar Blues” so, in essence, you will be able to play almost any blues song (in any key) when we’re finished with these next few lessons. That sounds promising, no? So, even though I can hear you groaning, “Man, he can’t even write a “Song For Beginner” in one part…” please take heart. In the course of three (relatively) short and painless lessons, you will have, literally, dozens of songs at your disposal, not to mention some good technique and a good start on leads and fills. I promise to not even mention the old saying about teaching someone to fish…

Once you start playing the guitar – learning the chords, figuring out how to strum, you now, the usual things- you also start learning music theory. “Learning” is perhaps not the right word. The theory is there all around you, but whether or not you decide to explore it and examine it and do anything with it tends to be a personal matter. For the most part, many guitarists do know theory, they simply do not know how to explain what they know. And yes, I guess that’s just a polite way of saying that they don’t know that they know it!

So let me say that this might be a good time for us to brush up on some basic music theory. If you haven’t already (or recently) done so, let me suggest that you read an old article or two – either Theory Without Tears or both The Musical Genome Project and The Power of Three before we start this lesson, if for no other reason than to get us all on the same page concerning terms.

Building The Blues

All set? Okay, believe it or not, we now have to learn a few more basic terms, specifically the bar (not to be confused with a barre chord) or measure.

As I’m sure you’re all aware of, music is counted of in terms of beats. In order to (a) create a universally understood language and (b) make it much easier to write out, musical notation and TAB, too, are written in such a way to divide the music into bars or measures. These are indicated by a vertical line running through the staff (in notation) or TAB lines.

The vast majority of music that we know is written in terms of four beats per measure. Yes, this is not an absolute, but in the case of the blues, you can pretty much count on it (no pun intended).

Some of you may also recall from other articles that I written that many songs tend to be written in terms of “phrases,” a phrase either being a line of lyric or a chord progression. Standard blues songs are written in three phrases of four measures each, which is what we call, appropriately enough, “twelve bar blues.” And you may not know it, but more than 80% of the blues falls into this category. And most of the rest are simple variations.

And you also may not know it, but twelve bar blues follows a distinctive pattern. Or falls into one of two patterns, I should say. We’re going to start out thinking in pure theory terms and then carry that theory into specific examples.

Pick a key, any major key. Your standard blues song will consist of only three chords in that particualr key: the “I” (which ever key you picked), the IV and the V. Let’s look at the two typical twelve bar blues patterns:

Take a minute and go over this. Let’s just look at the first pattern. You strum whatever chord you’re starting with (this is almost without fail the “key” in which you’re playing) and continue that for four measures (four separate counts of four). Then comes the IV chord, whatever that may be, for two measures, followed by two more measures of I. Then you have one measure each of V and IV and wind the whole thing up with two final measures of I. Nothing to it, right?

This is one of the many reasons why you can never scoff about knowing a little bit of theory. And is this case, a little theory goes an awfully long way. Think of all the chords that you know and try to think about how they apply to one another. If it helps, write yourself out a little chart like this (and I trust you’re capable of filling in the keys like Eb or F# by on your own…):

Now, you’re pretty much all set! If someone say’s “Let’s play Pride and Joy in E, using the first blues pattern, well, you wouldn’t even need me to write it out for you! But I will, just this once (and only the first verse). And, as an added bonus, I will add the measure count in parentheses:

Learning To Shuffle

Learning any blues song also provides you a chance to work on two important facets of playing – timing and what I call finesse. By finesse, I mean the ability to play just certain strings on your guitar and not bang away at all six strings at once (and if you’d like to read more about this, check out last fall’s column Just Because You Have Six Strings…).

The blues rhythm is usually referred to as a shuffle. To understand exactly how it’s done, you should familiarize yourself somewhat with timing. If you read music at all, I’m certain that you’re acquainted with the following notations:

Blues is more often than not played in 4 / 4 timing, which is when every measure (or bar) has four beats and each quarter note is one beat. The blues shuffle rhythm is based on triplets, but the middle note of each set is left out, leaving you with the following pattern:

Often times if you are reading this in a book, the author will write it out as a pair of eighth notes and have a remark somewhere on the page that a pair of eighth notes equals one of these triplet sets we’ve just spelled out (it is much easier than writing it out over and over (and over and over) again!).

Okay, that’s the rhythm, let’s get down to the actual notes themselves. Because we are just starting out, we are going to stick with the most basic shuffle for the time being. Next two times out we’ll look at a few of the more complicated variations. One thing at a time, okay?

Shuffling consists of playing a pattern of two pairs of simultaneous notes. The lower note is always the root (or I) of the chord you are playing. The higher note alternates between the V and VI of the chord. So, for example, if we were doing a blues shuffle on an E or an A chord, it would sound like this:

Nowhere near as complicated as you might have thought it would be, is it? Alright, then, let’s move on to our feature presentation. First off, let me mention that Before You Accuse Me is a twelve bar blues (big surprise there), but this follows the second chord pattern – the one where the second measure is the IV of the progression. Then let me also mention that while most people (even Eric Clapton on his Unplugged CD) play this in E, I play it in A. Why? Well, for starters, it’s not in my vocal range when done in E. This is one good reason to know your vocal abilities, as we discuss in this week’s guitar column (Singing In A New Year). The second reason is a bit more crafty and we will delve more into that next time out. So without further ado, let’s shuffle off:

As always, please feel free to write in with any questions, comments, concerns or even a song, riff or lead you’d like to see covered in a future “Songs For Beginners” article. You can either drop off a note at the Guitar Forums or email me directly at [email protected].

Until next week…

Peace

Honsing

September 9th, 2015 @ 4:35 am

Great lesson. Where is Part 2?

Paul Hackett

September 11th, 2015 @ 7:31 pm

Part 2 is here Roll Over Beethoven – Blues Shuffle and Fretboard Positions

Hope you like it too.

Brett

April 11th, 2012 @ 5:06 am

When I open a lesson it says “musical examples not available due to copyright restrictions in my region.” Is there any way around this?

Thanks,

Brett

David Hodge

April 11th, 2012 @ 5:37 am

Hi Brett

I don’t know how recently you’ve discovered Guitar Noise so my apologies if this may be old news to you. A while back, we were informed that our various song lessons were in violation of United States copyright laws and we promptly removed the tablature, music notation and lyrics from these lessons. Since then we’ve been in negotiation with various publishers, trying to work out a legal contract to use their artists’ copyrighted material. We’ve made some progress (currently we’ve gotten back nine songs) but it is going to be a continuing project. We hope you can be patient with us while we try to work things out.

Feel free to post any questions you may have or to email me directly at [email protected]. I look forward to chatting with you again.

Peace

Guitar Noise Staff

April 11th, 2012 @ 5:21 am

Hi Brett,

Welcome to Guitar Noise. Unfortunately we had to remove the musical examples from this lesson. We can only show the music for songs we negotiated a license for. You can view all the current lessons at https://www.guitarnoise.com/topics/easy-guitar-songs/

We’re adding new songs every month and we are still trying to negotiate the rights for lessons like this one. Hopefully you’ll still find a song you want to learn on this site.

– Paul