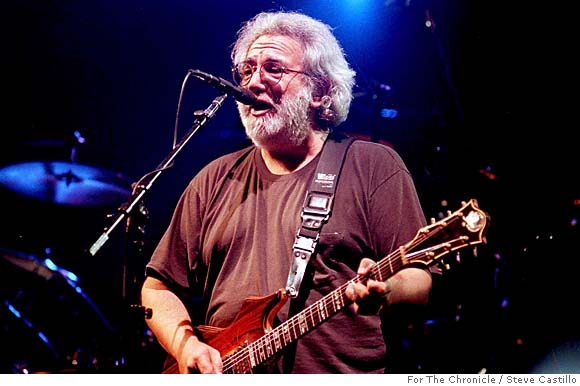

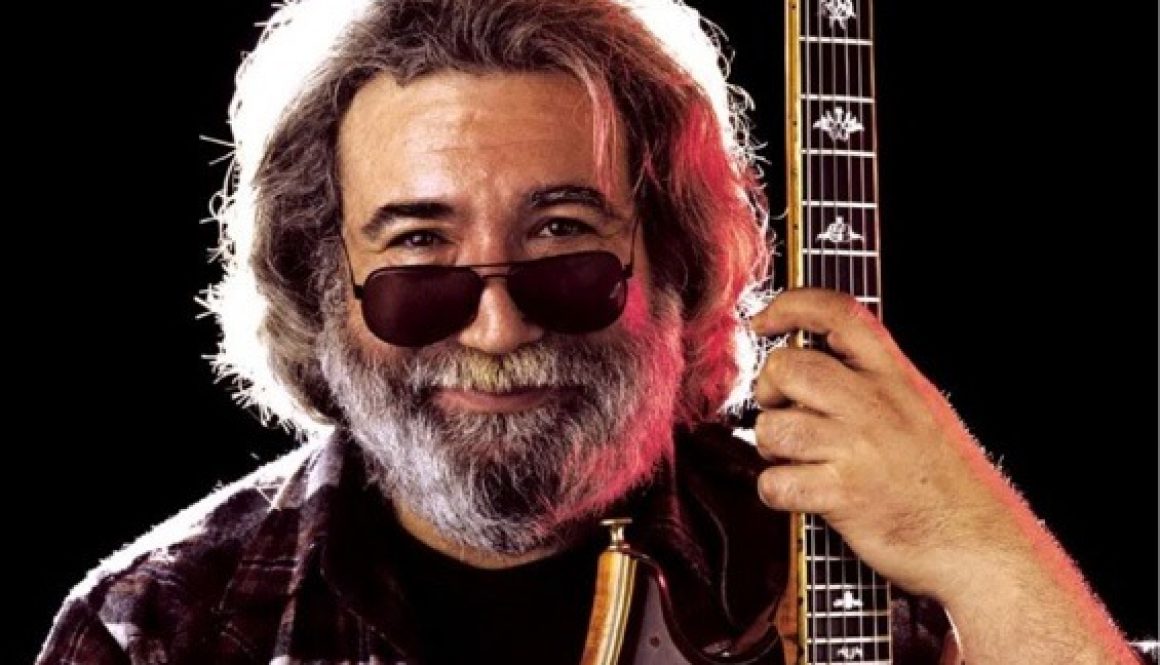

Jerry Garcia – Music Biography

The Grateful Dead are generally considered to be one of the greatest live bands of all time. They also boast one of the largest and strangest following of fans ever assembled. Deadheads, as they were known, represented a counterculture movement whose loyalty to the band spawned a sideshow capable of eclipsing anything the band ever did on stage. From 1965 to 1995 the band were superstars operating well outside the mainstream. Their lengthy improvisational shows forged a new relationship between themselves and the audience, giving birth to the jam band genre, and leaving no room for single guitar hero worship. But try to think of this band today and most of us have difficulty separating their amazing group achievements from the single iconic figure of Jerry Garcia.

Born on August 1, 1942 in San Francisco to musical parents, Jerry Garcia learned piano as a child until he lost part of his middle finger in a wood-chopping accident. After his father drowned in a fishing accident the following year he was sent to live with his grandparents where he heard country and folk music for the first time. This was the beginning of his lifelong obsession with country, folk and bluegrass music. He took up playing the banjo almost four years before getting his first guitar, a Danelectro, on his fifteenth birthday. His mother had actually gotten him an accordion which he convinced her to exchange for an electric guitar and amp at a pawnshop. His stepfather, who was also very musical, helped him learn some open tunings

Garcia dropped out of high school in 1960 when he was 17 and joined the army (as a punishment for stealing his mother’s car!), where he became serious about playing acoustic guitar. His leisurely approach to army life soon led to him getting discharged. Using his final paycheck he moved to Palo Alto where he began playing clubs and bookstores near the campus of Stanford University. It was here, while living out of his car, that he met the aspiring poet Robert Hunter, who would become his longtime songwriting collaborator. In 1961 he survived a near fatal car crash which served as a wake up call that got him to start taking guitar playing more seriously.

Fascinated with folk, bluegrass and old time country, he started to play for Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions in 1964. Other members of this jug band included guitarist and singer Bob Weir and singer/keyboardist/harmonica player Ron McKernan. With bands like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones dominating the airwaves in 1965, and even Bob Dylan going electric, the group decided it was time to switch to electric instruments. They renamed themselves The Warlocks and added Bill Kreutzmann on drums and the classically trained trumpet player Phil Lesh on bass. They soon became the house band for the public LSD parties held around the San Francisco Bay area known as Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests. Renaming themselves the Grateful Dead (owing to there already being a group in the area named The Warlocks), the band moved into a communal house at 710 Ashbury Street in San Francisco and were financed by the renowned chemist and LSD manufacturer Owsley Stanley. On the strength of many free concerts they built a large fan base and became a fixture on the local music scene playing at popular venues like the Fillmore Auditorium.

The infamous Summer of Love was in 1967 and the Dead, already one of the most popular bands in the Bay Area, released their self-titled debut album on Warner Bros. Records. They had little experience in recording music in a studio and the album was nothing like their psychedelic live shows. The album may have been a big deal in San Francisco but it was largely ignored everywhere else. They followed the album up with Anthem of the Sun in 1968 and Aoxomoxoa in 1969. Their interest in studio experimentation left them $100,000 in debt to their label. Bowing to the demands of fans they released their first live album Live Dead, which was recorded in 1969 at the Fillmore West in San Francisco. It was their first album that came close to capturing the true essence of the group in their improvisational psychedelic glory and sold well. Their fame outside of the Bay Area started to grow with performances at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 and at Woodstock in 1969. In 1973 they joined The Allman Brothers Band and The Band at The Summer Jam at Watkins Glen, which attracted 600,000 fans and was once in the Guinness Book of World Records for largest audience at a pop festival.

In 1970 they released two albums, Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty, which would become the band’s only real studio masterpieces. While American Beauty featured excellent compositions from everyone in the band, Garcia contributed some of his strongest songs ever: “Candyman,” “Ripple” and “Friend of the Devil.” Throughout the seventies and eighties the band would not release another album nearly as strong, and yet their following continued to grow to the point where it became it’s own subculture. Mythologist Joseph Campbell called Deadheads the world’s newest tribe. The band allowed its fans to record and share their shows, even setting up a taping section at all their shows. Deadheads followed the band religiously, compared notes on concerts and made a cottage industry of selling tie-dye t-shirts at concerts. If you were a Grateful Dead fan a concert was a religious experience. If you weren’t a fan, the whole thing was a resounding mystery.

Garcia’s highly improvisational guitar style reflected almost all styles of music, most noticeably the country and bluegrass of his early childhood icons. His melodic solos could reflect the sharp edges of James Burton or echo the lilt of a Celtic fiddle tune. He cited John Coltrane as one of his biggest personal musical influences.

In addition to the Grateful Dead, Garcia had numerous side projects, most notably The Jerry Garcia Band. He also worked with other bands. He served as an uncredited producer on Jefferson Airplane’s second album Surrealistic Pillow and added the signature pedal steel guitar to Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s “Teach Your Children.” As a solo artist he performed different styles such as jazz-rock, bluegrass, country-tinged rock and he even released an album of children’s music in 1993 called “Not for Kids Only.” Jerry Garcia is believed to be the most recorded guitarist in history, with thousands of live Dead and Jerry Garcia Band shows caught on tape, plus hours of studio work – altogether totaling more than 15,000 hours of recorded music.

As the bands most recognizable member, Jerry Garcia came to be viewed as a spokesman of the Hippie movement of the 1960s, not only for the Deadheads, but also the public at large. Although he totally dismissed himself as speaking for the band (or its fans), Garcia appeared quite amused by the band’s success. He once said:

“I feel like we’ve been getting away with something ever since there were more people in the audience than there were on stage. The first time that people didn’t leave after the first three tunes, I felt like we were getting away with something. We’ve been falling uphill for 27 years. I don’t know why. I have no idea. All I know is it’s endlessly fascinating, and incredible luck probably has a lot to do with it.”

The success of touring in a band that could sellout stadiums every night was not without its tolls. Garcia suffered from poor health owing to drug and alcohol abuse and an ongoing battle with obesity. He nearly died in a diabetic coma in 1986. In 1992 the Dead had to cancel 22 shows because of his ill health. The band’s tour still grossed $31 million that year, more than any other band except U2.

Garcia died of a heart attack just eight days after his 53rd birthday. As news of his death spread the Internet was flooded with eulogies and reminisces, while fans could be seen crying in the streets of San Francisco. More than 25,000 fans attended a memorial at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. His body was cremated and part of his ashes were sprinkled in the Ganges River in India and the other part in the San Francisco Bay.

“There’s no way to measure his greatness or magnitude as a person or as a player,” said Bob Dylan, who toured with the Grateful Dead in 1987. “He really had no equal. His playing was moody, awesome, sophisticated, hypnotic and subtle. There’s no way to convey the loss.”