Which chords should I begin learning?

Which chords should I begin learning and how should I practice switching from chord to chord?

Like most topics, there’s a lot of discussion about this, not only among both teachers and students, but most guitarists are willing to give you an opinion on it as well.

Before we delve into chords, though, I’d like to make a quick point that learning chords is not always the best way to start out, particularly for younger children. Many teachers advocate learning the notes within the first five frets on each of the strings before moving on to chords. There is some merit to this. For starters, it helps someone who’s not played a single note on the guitar before a chance to develop a little dexterity and also proper fretting technique. I think we’re all agreed that it’s usually easier to fret and sound a single note than a whole chord. For someone starting out, the inability to get a full sounding chord can lead to much frustration which, in turn, can lead to deciding that maybe the guitar is just too much trouble and not worth learning. For younger students, and also for some adults, the confidence gained by playing some single notes on various strings is all they need to make the next “step” into chord playing. We’ll be touching on this a little next time out.

If you use this technique with younger students, the next logical bit of progress is to introduce what many people call “cheater” chords. G, for instance, can be played with only one finger if you don’t play the fifth and sixth strings (fingering: XX0003). Likewise you can do a “half C” chord by only playing the notes on the first three strings (fingering: XXX010). This again is simply a matter of building up both confidence and good finger positioning. Believe it or not, I find that teaching the C and G major scales to be very helpful in the forming of chords. Once someone is used to using his or her fingers on certain frets to play the scales smoothly, it’s a small transition to learn to leave the fingers in place, thereby forming C, G and “middle of the neck F” chords.

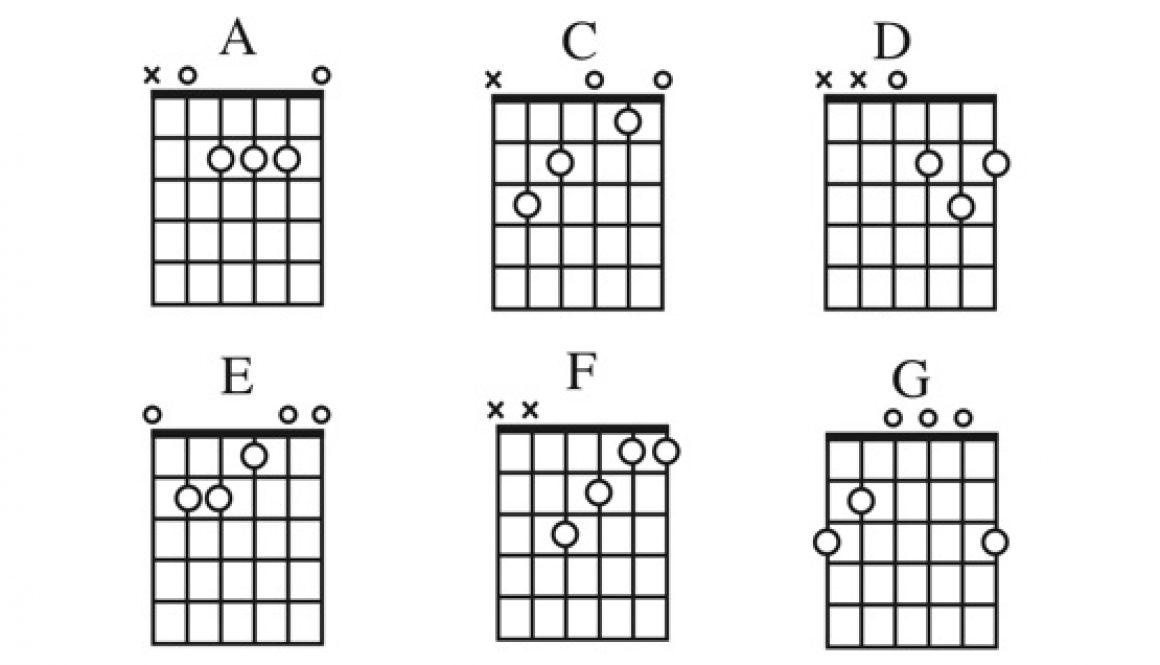

But when it comes to teaching chords in a more “traditional” sense, I tend to start out pretty much the way I describe in Guitar Noise’s Absolute Beginners article – Absolute Beginners Part 1: Chords. E minor is first chord we learn, followed by E major, A minor (which is the same fingering as E major), then A and then we stop for a bit. D major and B minor come next and then we’ll finish up with C major and G major. I know a lot of teachers prefer to use “two finger” chords first, E minor, E7, A7 and Am7, and, depending on the student, I may indeed stick with those at first, particularly as they lend themselves very nicely to learning to change between chords.

And speaking of which, it’s kind of silly, to me anyway, to teach chords without going over transitions. That’s why I’ll usually teach Horse With No Name right at the start. I want a student to get used to the idea that chords are supposed to have movement and that movement should be, for the most part, rhythmic and regular. So switching between the Em (022000) and the “horse chord” (200200) is just another way to get a beginning guitarist started in a friendly and easy manner. We will also work on changing from E minor to E major and, if things are going well, from E major to A minor.

When working on transitions, I find the best thing to do is to start by giving each chord eight beats, usually all downstrokes, and then changing to our new chord for another eight beats and then changing back. It’s important to do this in a steady rhythm since most chord changes occur in a song setting (which, to no one’s surprise I’m sure, is rhythmic). For me, I’d rather have the student miss getting all the notes right but keep the rhythm steady than to stop the rhythm in order to reset their fingers. That’s why I don’t care how slow we start out, tempo-wise. Chord changing, like most things about the guitar (and so many other things) is truly a matter of repetition and practice. It will come with time and patience. Good rhythm skills, though, are hard for a lot of people to come by and that’s why I stress them so much in learning to change chords.

If a student has gotten to the point where the “eight beat chord change” is comfortable, then we’ll move to changing the chords every four beats, then two, and finally changing on each beat. This may take the student a while, but there are all sorts of other things to be learning in the meantime.

Usually, I’ll group the chord changing exercises by pairs, E minor and E major, E major and A minor, A minor and A major, E minor and A major, E major and A major. As I’ve mentioned, the seventh chords are easier for some students when starting out. Then we’ll try to switch back and forth between three different chords. There are so many songs that involve only the E, A and D chords that most people know. Wild Thing comes immediately to mind for some reason. And any blues song in A is now playable to most beginners.

There are two things (three really, but the third is part of the second) I’d like to quickly add to this discussion. First, chord changing is something that can be done quite easily during a person’s “free time.” By this I mean why watch a football game without your guitar? You don’t even have to strum it (although I recommend you do) to work on changing between the chords. If it’s too noisy, then do it during the commercials. That’ll give you easily ten minutes practice out of every thirty of a program.

Second, I almost always start teaching beginners about the roots of chords as we learn them. This way we cannot only learn what strings to strum or not to strum (like the low E (sixth) string of the D major chord), but we can also learn what I call the “bass/strum” technique. This is simply hitting the root note of the chord on the first beat followed by the full chord on the next three beats of the measure. Because I teach the E, A and D chords first, this is a fairly easy concept for most students to get. It’s also a little sneaky because hitting the open-stringed root note first gives the student a little extra time to get the rest of the chord in place.

My other reason for teaching the “bass/strum” is that when we get to the C and G chords, as well as others where the root note isn’t an open string, the student is conscious of the need to get the bass strings in place first. This isn’t as easy a thing to teach. If a guitarist learns to make a G chord by placing his or her fingers on the high E (first) string first, then that is often how he or she will try to switch the chord in transition. And because most of the time you switch a chord on a downstroke, this can lead to all sorts of rhythmic hiccups.

Beginners should definitely check out the article Absolute Beginners Part 1: Chords.