A (very basic) Primer for Walking Bass Lines – Connecting The Dots – Part 1

We’ve mentioned this before, but it certainly bears repeating. The major difference between someone who is an absolute beginning guitarist and an “early intermediate” player, if you will, is that the more experienced player, who may not know more chords than the beginner, knows more interesting ways to make a chord change. It’s all in the little touches, and even though these little touches may seem like a huge step forward for a beginner, most of them are actually quite easy.

One of the more simple bits of this seeming magic is the walking bass line. We’ve used it in a number of our song lessons here at Guitar Noise, such as Friend of the Devil, Eleanor Rigby and (Sitting On) The Dock of the Bay. There’s even a little bit of a walking bass line in one of the versions of House of the Rising Sun lesson.

What we’re going to do here is to look at the basics of putting together walking bass lines. While we’ll cite specific songs and examples to help understand them, we’ll put more of our focus into looking at how to glean enough information from other sources, such as chord progressions and timing, so that we can create our own walking bass line fills. The idea here is to give you enough knowledge and confidence so that you can have this “little touch” at your beck and call.

This will be done in a series of lessons, both Guitar Columns, such as this one, and in upcoming song lessons (both in the Easy Songs for Beginners and the Songs for Intermediates sections) as well. In the columns, we’ll focus specifically on the walking bass lines, while the song lessons may touch upon other subjects as well. They tend to do that, don’t they?

Starting With Our Roots

First, and I can already hear your eyes rolling in your head, if you seriously want to be good at this, you are going to need to have a little bit of theory under your belts. Not too much, so don’t worry. Your reputation as a “self-taught guitarist who doesn’t need to know how to read music or know any music theory at all for that matter” will be safe with me. After all, we all know how important image is!

But you will need to know some things – simply iterating our topic, “walking bass lines,” points that out. If we’re “walking,” where did we start from? Where are we walking to? How long is it going to take us to reach our destination? Are we expected to arrive at a specific time? What route, path or trail are we going to take to get us there? Are we going to stop for lunch along the way?

All good questions, yes? And the answers are all dependent on many factors. But, for starters, let’s begin with the most basic of ideas in order to tackle the first question.

As you already know, every chord is made up of notes. What you may or may not know, depending on which Guitar Noise articles you’ve read or how much you’ve learned from other teachers, books, DVDs or other tutorial sources, is that each note of the chord has a function. For the moment, we’re concerned with the root note of any given chord. Simply put, the root note is the note of the chord that bears the same note name of the chord.

Okay, maybe that’s not so simple on the surface, but, trust me, it really is! The root note of an E major chord is E. The root note for C major is C. The root note for C minor is also C, because “minor” is a chord name and not a note name (and if you don’t know or remember your note names, run right over to any of our beginning theory lessons, such as The Musical Genome Project, and come right back). The root note for Cm7(b5)? If you said “C,” and I hope that you said it without any hesitation or quiver in your voice, you’re absolutely right! Okay, here’s a trick question: What’s the root note for the chord F#m7? Hopefully, you said “F#” and not just “F,” since F# is a note name. You have to include any sharps or flats if they are with the initial name of the chord. So the root of Bb7(#9) is, you guessed it, Bb.

So now that we know where we’re starting from, where should we go? The easiest way to start thinking about our walking bass lines is by looking at the root note of the chord we’re at to begin with, and then look at arriving at the root note of the next chord in our progression. Yes, there are (many) other paths down which we can choose to walk, but for now let’s concentrate our efforts here.

The Key Parts: Time And Place

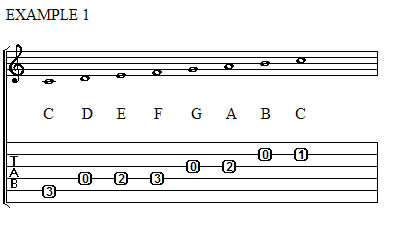

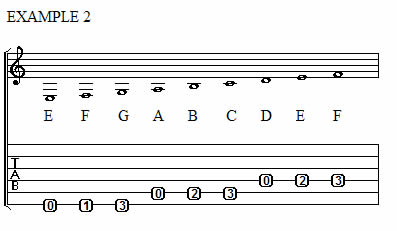

Since we’re concentrating on moving from the root of one chord to the root of another, it’s also a good idea to work within the key of the song (or progression) in question. Again, I can’t stress enough that this is simply one of many ways of going about putting together a walking bass line. But I think that if you can grasp what we’re trying to do here, you might find some of the more “exotic” routes easier to navigate. How about we start with the key of C, just so we can take a look at our C major scale for old time’s sake?

Now (hopefully) we’re all aware that we can extend our C major scale on either side of these notes. Since we’re talking about walking bass lines, we’re obviously more concerned with the lower notes, those on our low E (sixth), A (fifth) and D (fourth) strings. So let’s just focus on those for the moment, shall we?

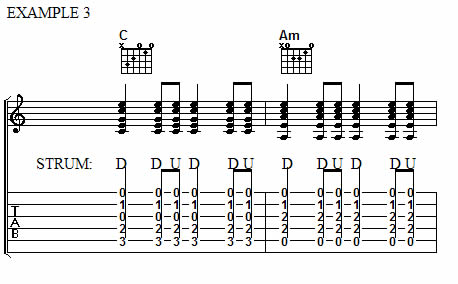

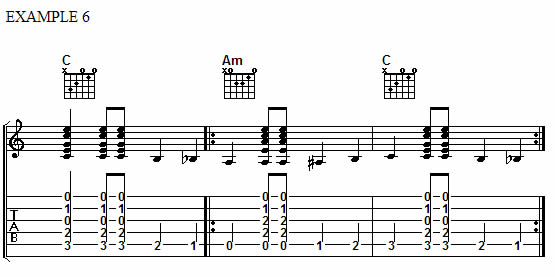

So far so good! Now we need a progression to work with. Let’s continue keeping things simple by working with one measure of C followed by a measure of Am. Maybe something like this:

Okay, this would be a good place to good over our questions:

Where do we start from? We want to start with the C, since it’s the root note of the C major chord.

Where are we walking to? We’re walking to A, since it’s the root note of the A minor chord.

How long is it going to take us to reach our destination? Are we expected to arrive at a specific time? You may have thought I was being frivolous in asking this, but now you see that these are, pardon the pun, key questions. Ideally, we want to hit that A note when we switch chords, so we want to arrive at it on the first beat of the second measure. And since it would be nice if we could keep some of the chord strumming while we do it, let’s try this:

Nothing too complicated here. We start with our basic pattern and substitute individual C and B notes for the third and fourth beats of the first measure. We could go with a full Am chord for the first beat of the second measure (as we have in Example 3), but it can’t hurt at this point in the proceedings to hit yourself over the head with the bass notes in order to hear exactly what you’re trying to accomplish.

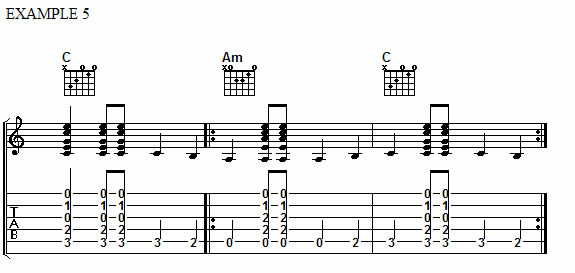

Now let’s try reversing directions:

As I keep mentioning, this is simply one way to get started. If we wanted to, we could incorporate noted from outside of the C major scale to make things more interesting. Here’s one way we could do that:

Seeing The Signs

I think it’s important to take a moment here for a bit of sidestepping. One of the (many) things that fascinates me no end is the very amusing paradox of many guitarists’ (and aspiring guitarists’) mentality. On the one hand, possibly no other musician celebrates not knowing anything about music more than the guitar player. We don’t have to read music. Our heroes didn’t read music. We don’t need to know theory. You get the drift.

On the other hand, many of these same guitarists go way out of their way to label things that other musicians don’t even worry about. In Example 5, for instance, many guitarists wouldn’t even bother attempting that simple walking bass line unless someone had noted that the chord progression was C, C/B, Am. Without the slash chord (for more on slash chords, please see the Eleanor Rigby lesson) it might not ever occur to them.

The point here is to make sure you know to not depend on the music to spell out everything for you. You want to learn for yourself where and when to put in walking bass lines to make your music more interesting and less mechanical.

You should always be on the lookout for signs in the music or chord charts that indicate favorable chances to toss in a walking bass line. What sort of signs? Well, in our example, we’ve used a very simple bass line to go from C to A and then back again. In the musical alphabet, those notes are two letters apart. So whenever I see two chords whose roots are two notes apart, whether those two notes are two whole steps or a step and a half apart, then I think about using something along these lines when playing. Doesn’t matter if the chords are major, minor, sevenths, or what have you. Typical chord changes that you’ll see in a lot of guitar music are:

- C to Am (or A or A7)

- G to Em (or E or E7)

- D to Bm (or B or B7)

- F to Dm (or D or D7)

- A to F#m (or F# or F#7)

- Am to F

- C to E (or E7 or Em)

- G to B (or B7 or Bm)

- D to F# (or F#7 or F#m)

- A to C#m (or C# or C#7)

There are, of course, many others. Also it’s important to remember that these bass lines can travel in either direction. You’re not limited to a one-way trip.

To walk from your first chord to your destination, try to keep two things in mind: the “route” or “path” you want to take and when you want to get to your destination. More often than not, it’s good to use the old “shortest distance between two points” method, using your root note from the first chord as the starting point, the note in between as the second step in your walk and then arriving at the root note of your destination chord. But it’s also important here to take into account the key of your song. For instance, if you’re going from G to Em, use F# as your middle step, not F. Likewise C# sounds a lot better when going from D to Bm because C# is part of the D major scale (which has the same notes of the B natural minor scale).

As for time of arrival, getting there when the chord changes is usually the best strategy, but there are others. The (Sitting On) The Dock of the Bay lesson gives you a great example of the use of anticipation, or arriving just a tad earlier than expected. Anticipations can give a very interesting twist to a walking bass line.

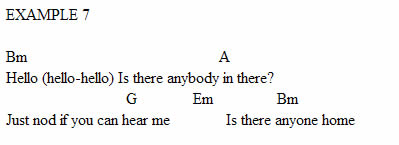

Here’s an example that might bear this out. If you look at most chord charts for Pink Floyd’s Comfortably Numb, you’re likely to find this for the verses:

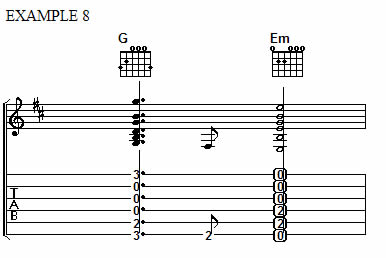

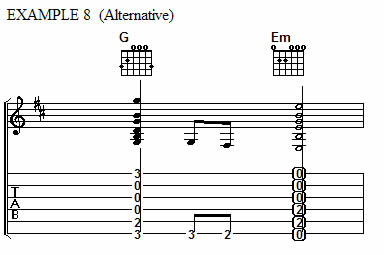

Given that we’re going from G to Em, it’s not too big a stretch to try something like this:

You can hear, even on an acoustic guitar, that this bass line provides a lot of punch. And punch is precisely what we’re looking for in this instance. We start out with our G chord and then pound that F# note at the second fret of the low E (sixth) string a half beat before reaching the Em chord. For those of you who like flailing away at the bass notes, you can be less subtle by giving the G root note of the first chord an extra hit before moving on to the F#, as demonstrated in “Example 8 (alternative).”

Before anyone writes to tell me, I know that this is not the chord voicing used on the original recording. If memory serves me correctly, the G is done 32003X and the Em is actually an Em7, played 02003X. For the purpose of this lesson, I’m trying to keep things simple and have opted for an easier arrangement. Might as well save the real voicings for an Easy Songs for Beginners piece, no?

And speaking of adding a little spark, in the chorus section, you’ll find a number of A to C chord changes:

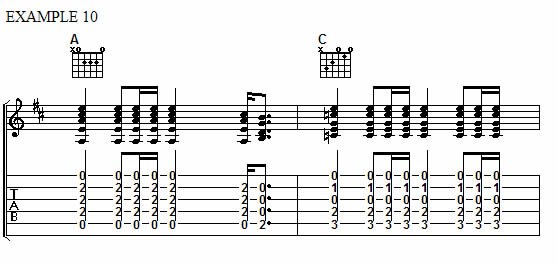

And here’s a cool trick to handle those:

Even though our intent is to spice up the A to C change just by walking up the bass notes from A to B to C, we’re able to do a lot more than that in this case. In essence, we’re using the B note in our walking bass line, plus the guitar’s standard tuning to create a very cool sounding chord change. On the fourth beat of the measure, hit the A chord on a downstroke, pull off your fingers, hammer the index finger on the second fret of the A string (to get the B note in the bass) and play a short upstroke, hopefully one that misses the high E (first) string. All of this happens in the blink of an eye, so take heart if you need a little practice to sort it all out.

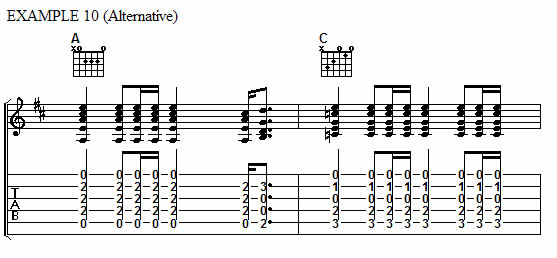

Technically, just to appease all the “I need everything spelled out even though I don’t need theory” crowd, this passing chord is G/B. You can also play it as shown in “Example 10 (alternative),” which adds a D note at the third fret of the B string. Personally, I find this harder to do on the upstroke and when I want to play this change in this fashion, I’ll use two very quick downstrokes. Both ways, as you can hear in the previous MP3, sound perfectly fine.

I hope that this brief introduction to walking bass lines whets your appetite for more. As mentioned earlier, we’ll be looking at this in a series of columns and song lessons (both Beginner and Intermediate) that will be going up online over the next few weeks. And don’t forget to look at some of the old lessons to get more information on the subject.

As always, please feel free to write me with any questions. Either leave me a message at the forum page (you can “Instant Message” me if you’re a member) or mail me directly at [email protected].

Until next time…

Peace

Ciaran

January 7th, 2017 @ 6:18 pm

Wow really great information and well laid out thanks for taking the time to put this together