Tales From the Ili Valley

Recently I participated in a cross-cultural experience that was far removed from playing or teaching guitar. I traveled to a remote area in northwest China to produce a documentary about the people who live there. During the six weeks of production I learned more than I could hope to fit into one article. There are three important things I learned, however, that are worth sharing today.

The first concerns making movies. I learned that making movies on location means you can’t eat when you are hungry, can’t sleep when you are tired and when you need to go to the toilet … well.

The second concerns making movies in China. If you are planning to interview people in China don’t expect everyone to be able to speak Chinese. This was perhaps our biggest surprise and obstacle.

The third concerns music. Often it is not so obvious, but what David Hodge says in On Gifts and Giving is true: “Music is a medium that really works when it is shared.” This became apparent when our multi-lingual and multi-national film crew of four found itself in a remote part of the world where there was no common language for communication.

The People

The region we visited was northwest China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. In English Xinjiang literally means “New Territories” or “New Frontier”. While the region covers 1/6 of the worlds most populated country only 15 million people inhabit it. That is roughly half the population of Canada. The local population is comprised mostly of China’s major ethnic groups the Kazaks, Kygyz, Daur, Tajik, Uzbeks, Mongols, Sibo, Russian and Uyghur (pronounced wee-gur).

Our film was concerned mostly with the Muslim Uyghur people. Quite different from Han Chinese, Uyghurs have their own language, culture, customs and music. They originally arrived in Xinjiang from the grasslands of Mongolia and converted to Islam from Buddhism sometime before the 8th century. Originally descended from the Turks, the Uyghur spoken and written language still closely resembles Turkish today. Their traditions, customs and music are also very similar

The Ili Valley

Throughout Xinjiang are some of the key staging posts of the ancient Silk Road. Not far from the border with Kazakstan is the Ili Valley, a quiet place geographically isolated from the rest of China by the the formidable Tianshan mountains. Most people are here are Muslim and few speak China’s official language. This part of the world receives very few visitors. In fact, this particular area of China was not officially open to foreigners at the time we visited. That does not mean, however, that the local people do not welcome outsiders.

One gets the impression that the Uyghurs living here survive much the same way as they have for centuries. In their small farming communities people work the land that has been passed down to them from generations before.

The Gift

Our movie is about the lives of Xinjiang people today. Staying in Uyghur homes while making a movie about their lives turned out to be a special gift. While we were in Ili we lived very closely with the local people. We stayed in their homes and ate their food. During the day we went out on the farms with people. We were invited to the neighbor’s homes and even went to a wedding. Communication relied on means other than language. No one could speak English and only a few could speak a bit of Chinese. We played with the children and made games out of them teaching us their language. We wanted to learn as much as we could in the little time we had.

At the end of each day everyone would gather after dinner to talk. After we had wrapped up shooting for the day we would turn the camera around. Using a little TV screen that pops out of the side of the camera we could show them everything we had recorded that day. As most homes were without electricity let alone TVs this was the first time people could see themselves on camera. Not only were they delighted to see their daily lives and habits captured on tape, but also they got a chance to see how we viewed them. They saw what they looked like to the outside world. We also spent a lot of time teaching people we met how to use our camera. It was a great experience to turn the camera over to them so they could film their family and friends and later watch the results.

Everyone in our film crew was also a musician. We took special interest in local music everywhere we went. We tried to record as many live musical performances as possible. In addition to a video camera we also had an MD player with us. We recorded a great deal of local songs performed by local musicians. Most of them were farmers or laborers who were more than happy to perform for us. Capturing them on tape It was better than recording any of the professional musicians we met.

The most enchanting moments always came after the performances. When we had finished recording we would immediately give a set of headphones to the performer and let them listen. It was the first time they had ever heard themselves sing and play. They were delighted at what they heard. It was not the ingenuity of the technology we brought, or the complexity of such small machines that awed them. Their eyes shone when they heard their own voices and instruments for the first time. They like what they were hearing.

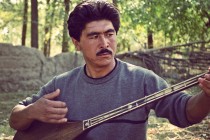

Our good friend Moidun, a farmer from the Ili Valley, played many songs for us in the apple orchard behind his house. Moidun’s instrument is a two string duntar. It is a simple yet elegant instrument with both strings tuned a fifth apart and tuned to match his voice. The local songs he sang for us gave us the true flavor of the Ili Valley. When he heard himself on the MD recorder the first time he laughed, and immediately passed the headphones to his friend. “Hey. That’s me,” I am sure is what he said. “I sound really good, don’t I?”

When it was time to leave this quiet valley parting was difficult. We had been there four days already and no one would accept money for all the trouble our presence had caused. We ate and slept for free, and people had even taken days off work to show us around. In a short time we had become good friends with all the people who welcomed us. There were invitations to stay for a few more days, and pleadings to eat at least one more meal before we left. In the end we were extended the warmest invitation imaginable to return anytime. Whether it is a year from now or ten, they will be waiting for our return someday.

Now in the part of the world where I live the weather is starting to get cold. All indications are that it is going to be a long, cold winter. It is comforting to know that somewhere in one of the world’s most remote and isolated corners I have made friends and they are waiting for my return.